I finally finished reading Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Although it took me four months to complete it in the end it was an amazing book and it caused me to think deeply about my own national and ethnic identities.

The book featured two main characters, Ifemelu and Obinze, who immigrate to different countries from Nigeria. Ifemelu goes to America and Obinze travels to England. I found myself relating to both characters.

In three weeks I'll be moving from California to London, England to complete a one year Masters program.

I'm excited but also anxious. And yet, I can't imagine that my anxiousness at all equals to those who want to enter England from the Commonwealth or the Global South.

One night while I was reading Americanah I took out my blue American passport and my red United Kingdom passport and just stared at them and thought about my dual citizenship. Arguably, I possess the two most powerful passports in the world. And that's a legacy of immigration.

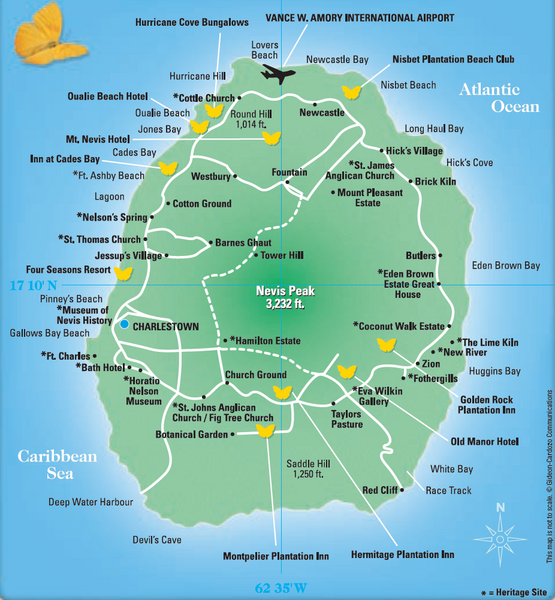

My father was born in Nevis. Nevis is a tiny island in the Caribbean that used to be owned by the British. It didn't receive its independence until 1983. My dad's story is so eerily similar to Obinze's that I had to pause continually while reading the novel.

My father didn't have a terrible life in the Caribbean. His family was middle class by island standards. His mother ran her own private school where the children of government officials attended. His father had a government job and also farmed. All of the children attended school although it was common for kids to be pulled out to help their parents with farming.

In all truth, middle class cannot be at all compared to a social class in America.

If you take a materialistic approach then middle class there is lower than low income in America. My father had no electricity and no running water growing up. A fact many Black immigrants will remind you of as a way to put unfair expectations on their American born children and to denigrate Black Americans. This is the uncomplicated truth because then there's the fact that he had community structure. He didn't live in the midst of violence (instigated by gangs or the police). He received a quality education. Perhaps even superior to most schools in America even though they had less materials and worse buildings. He had clean food to eat. These are all things that in America are mainly accessible to the (white) middle class.

Also, living in a Black majority country brings different issues. White supremacy is more of an invisible hand in the form of colonialism. This means that your country is dealing with less collective opportunity for its citizens because of the interference of leech-like European colonialist forces. It also means that the same issues of experienced day to day anti-Blackness is in many ways a non-factor. You're not really "Black" in the American or European meaning until you go to an American or European country.

My father nurtured a desire to move to America from a very young age. Perhaps it was a similar desire to Obinze's. It wasn't that life was horrible or desperate in the Caribbean. It was more that there was increased opportunity abroad. My father was of the social position where he was acutely aware of his glass ceiling and he wanted more. Obinze, the child of a Nigerian university professor, was in a similar situation.

My father tried to gain entrance into America but they rejected him. America has always had a strict immigration policy when it comes to Black majority countries. Many of his friends were going to Canada but they rejected him as well. So then he tried England and was accepted.

My father was accepted into England because Nevis is a part of the Commonwealth. At the time there were no restrictions against Commonwealth citizens who desired to move to England. He went during the 1950s. Actually not long after the 1948 MV Empire Windrush (the first mass arrival of Caribbean people to London).

He worked on the path towards citizenship and then left to go to Canada. And from Canada he was able to gain entrance to the United States on a work permit. Three countries later and he had finally reached his end goal of being in America and legally becoming American. He then went back to England for a second time in the 1980s and this is when he met my mother.

Unlike my father, my mother was born in England. She was born to Jamaican parents who similarly to my father had immigrated during the time when there were no restrictions. After my father and mother married they decided to move to America because my father was still convinced that it was the best country in the world. And then I was born a few years later.

For a long time I didn't want to reconcile with my complex national and cultural heritage. At first I just wanted to be Caribbean because I had internalized negative views about being Black American. I didn't understand why racial inequality functioned in the way it did. And neither did my parents. My father came to America with his narrative and didn't care to figure out the narratives of native born Black folks.

But as I began to feel more and more alienated from my Caribbean heritage (due to never being around Caribbean people except for my parents) I started to embrace being a Black American. And I started to claim my Black American-ness at the expense of all my other identities. I was ashamed of my being raised to be anti-Black American. Simultaneously, I was enamored with what I was learning about Black American history. I had read the Autobiography of Malcolm X and I wanted to claim that legacy especially since all I knew was being Black in America.

My curiosity about exploring the nuance of my identities probably only began two years ago when my maternal grandmother passed away. My Jamaican grandma who I'd visit every other summer in England. She'd always have to speak slowly because nobody taught me how to understand never mind speak patois.

When she died I felt a weird emptiness that went beyond no longer having the only grandma I ever knew and loved. I also felt like I had lost my one genuine connection to being Caribbean. All my life my father had been so into becoming American -- to talking about how great America and England are -- that he never taught me a firm respect for the islands.

My grandma, by contrast, never tried to become English. Maybe that's why after forty-something years she never lost her accent and all of her children could speak and understand patois. But I had been forced into acculturation. I was forced to see myself solely as American and yet to view being Black American negatively.

After I lost my grandma I felt like if I understood my heritage then I'd be better able to understand her legacy. So I started reading and studying.

Then my uncle invited me to stay in England with him after college graduation. And I eventually decided to apply to postgraduate programs. And here I am.

Americanah reminded me of the complexities of my heritage. Transnational boundaries. The complexities of being American. Why it makes sense for so many Black immigrants to be low income in this country when they were middle class at home. The incessant push that education is the means to class advancement. The unrealistic expectations put on American or English born children. The seemingly mutually exclusive nature of being Black American and a Black non-American. The legacy of colonialism and imperialism.

I have a lot left to discover but it's an exciting journey. Going to England is a way for me to become closer to my roots.

Are you fantasized about interracial dating? Do you want to have a partner from another race or ethnic group? If yes, then you have come to the right place. MixedRelationship.com

ReplyDelete